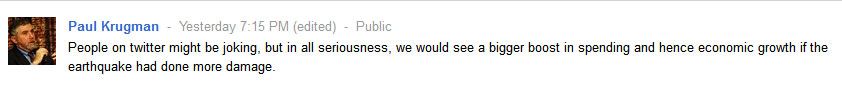

Greater Earthquake Damage Would be Better

In response to the Virginia-based earthquake that rattled up the east coast on Tuesday, 8/23, we have a Nobel Prize winning economist claiming that we’d have more economic growth if the earthquake had been bigger and had broken more stuff. Despite that statement making me uncomfortable, perhaps there's some logic to it. The damage caused would have to be addressed -- buildings rebuilt, roads repaired, cars replaced, and so on. People would have to be hired to do that work, and we could certainly use less unemployment, right? The materials suppliers would have more orders to fill, those new hires doing the work would earn a paycheck which they spend on goods and services, which in theory would grow the economy. The problem is that viewpoint ignores half the story.

In Economics 101, we learn about “The Broken Window Fallacy”, a parable written by Frédéric Bastiat, an 1800’s economist from France. The parable is meant to highlight “the seen” vs “the unseen”.

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper, James Goodfellow, when his careless son happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at such a scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate owner this invariable consolation—"It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass were never broken?"

Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory, which it will be well to show up in this simple case, seeing that it is precisely the same as that which, unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical institutions.

Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier's trade—that it encourages that trade to the amount of six francs—I grant it; I have not a word to say against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and, in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is that which is seen.

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, "Stop there! Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen."

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another. It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace, he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added another book to his library. In short, he would have employed his six francs in some way, which this accident has prevented.

So the shopkeeper began this parable with a window and 6 francs, and ended with a window and no francs. By all accounts the shopkeeper is poorer as a result of these events. The same could be said in the aftermath of disasters (natural or man-made) -- a great deal of economic resources are spent simply getting individuals back to square one. To call that economic growth is to ignore the loss suffered by those individuals. If long-term economic growth could be achieved simply by the rebuilding of destroyed property, then we should all go out tonight and torch every home in the country. Imagine the economic growth that would follow.

Update: Apparently the Krugman Google+ account turned out to be a fake, the message is not all that off given that he thinks an alien invasion would be a boon to this economy.